Lecture 12 - Multilevel Models

Rose / Thorn

Rose:

Thorn:

Repeat Observations

for any given estimand, there are multiple estimators we can use (but some are better than others)

can include categorical responses such as individuals as seen before

- but the model is not learning

Multilevel Models

- models within models

- model observed groups/individuals

- model of population of groups/individuals

the population model creates a kind of memory

multilevel models with memory learn faster, better AND models with memory resist overfitting

multilevel models use every observation to inform predictions about other cafes and the population of cafes

prior for next individual is the posterior of the previous one

Regularization

multilevel models adaptively regularize

complete pooling: treat all clusters as identical -> underfitting

no pooling: treat all clusters as unrelated -> overfitting

partial pooling: adaptive compromise that achieves regularization

Reedfrogs

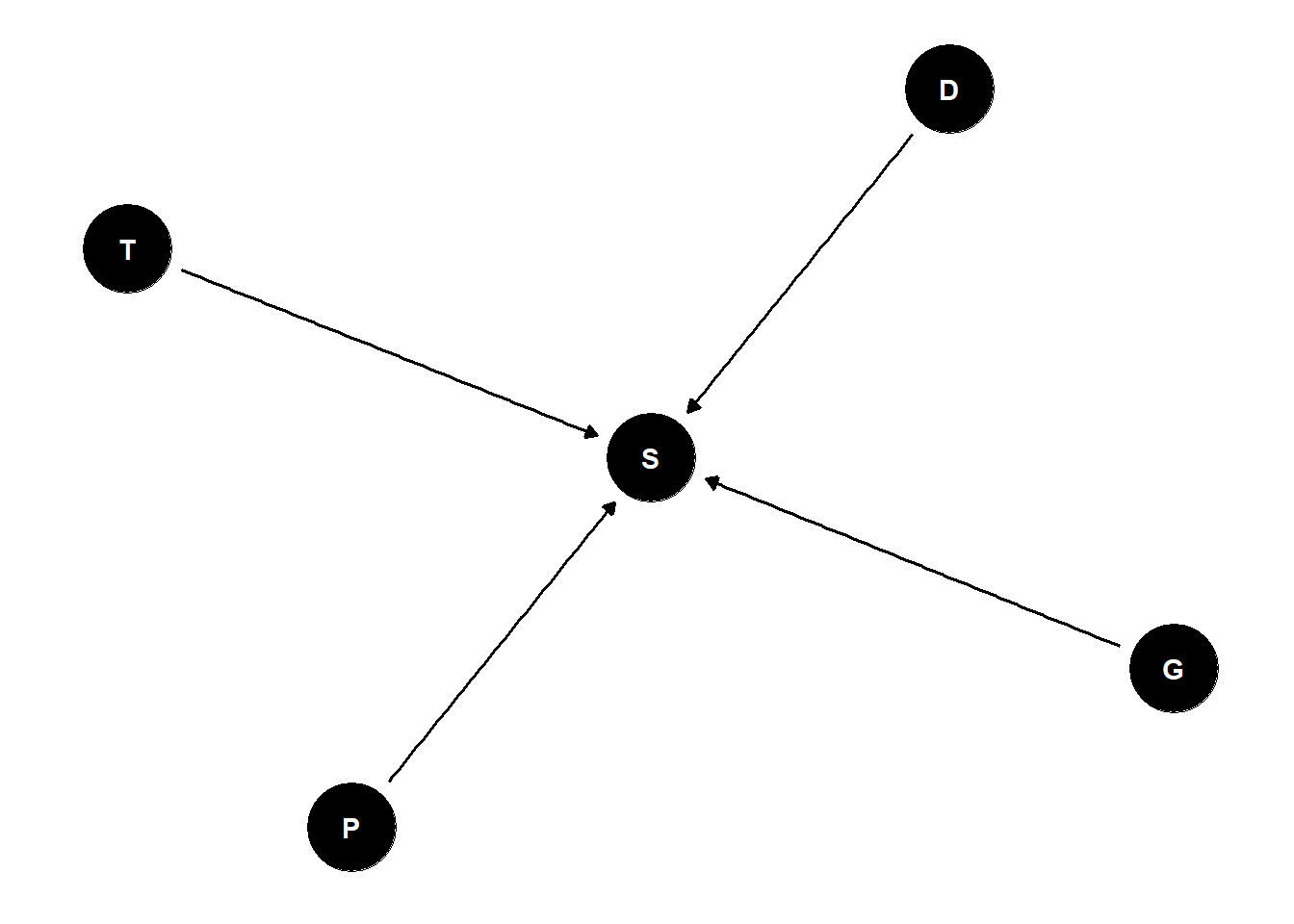

treatments: density, size, predation

outcome: survival

48 groups (“tanks”) of tadpoles

\(S_i \sim Binomial(D_i, p_i)\)

\(logit(p_i) = \alpha_{T[i]}\)

\(\alpha_j \sim Normal(\overline{\alpha}, \sigma)\)

\(\overline{\alpha} \sim Normal(0, 1.5)\)

parameters are just unobserved variables

- data is an observed parameter

if we want to learn about differences in between groups, we can set the prior for the mean tank as we normally would and then leave the prior for the variation of the groups as an unobserved parameter to be learned

find optimal value of sigma through cross-validation

- although we are using the model to choose a prior, we are not basing it off of model fit of the sample, we are evaluating it on cross-validation (out-of-sample). So we we are just assessing whether the model is overfit - not seeing how well it fits the data/causal relationships

Automatic Regularization

can use automatic regularization instead of cross-validation to remove the need to run so many models

\(S_i \sim Binomial(D_i, p_i)\)

\(logit(p_i) = \alpha_{T[i]}\)

\(\alpha_j \sim Normal(\overline{\alpha}, \sigma)\)

\(\overline{\alpha} \sim Normal(0, 1.5)\)

\(\sigma \sim Exponential(1)\)

library(rethinking)

data(reedfrogs)

d <- reedfrogs

d$tank <- 1:nrow(d)

dat <- list(

S = d$surv,

D = d$density,

T = d$tank )

mST <- ulam(

alist(

S ~ dbinom( D , p ) ,

logit(p) <- a[T] ,

a[T] ~ dnorm( a_bar , sigma ) ,

a_bar ~ dnorm( 0 , 1.5 ) ,

sigma ~ dexp( 1 )

), data=dat , chains=4 , log_lik=TRUE )

mSTnomem <- ulam(

alist(

S ~ dbinom( D , p ) ,

logit(p) <- a[T] ,

a[T] ~ dnorm( a_bar , 1 ) ,

a_bar ~ dnorm( 0 , 1.5 )

), data=dat , chains=4 , log_lik=TRUE )

compare( mST , mSTnomem , func=WAIC )multilevel models regularize “for free” - model mST is a multilevel model and having sigma as a prior means that it is regularized around the relevant values

mSTnomem is not a multilevel model (sigma is not a prior - it is a fixed value)

when you are working with multilevel models, when you add treatment variables, the variation among means is going to shrink because you are accounting for the variation with the different treatments

multilevel models often have lower neff than non-multilevel counterparts with more parameters because the parameters are hierarchically imbedded and operate more efficiently – it is the structure that matters not the absolute number of parameters

- adding parameters to a mlm doesn’t necessarily result in overfitting because of this fact, they are resistant to overfitting

more evidence results in more accurate modelling - however individuals furthest from the mean have results that have the most discrepancy because the model is skeptical of extreme events

stratify mean by predators:

\(S_i \sim Binomial(D_i, p_i)\)

\(logit(p_i) = \alpha_{T[i]} + \beta_PP_i\)

\(\beta_P \sim Normal(0, 0.5)\)

\(\alpha_j \sim Normal(\overline{\alpha}, \sigma)\)

\(\overline{\alpha_j} \sim Normal(0, 1.5)\)

\(\sigma \sim Exponential(1)\)

# pred model

dat$P <- ifelse(d$pred=="pred",1,0)

mSTP <- ulam(

alist(

S ~ dbinom( D , p ) ,

logit(p) <- a[T] + bP*P ,

bP ~ dnorm( 0 , 0.5 ),

a[T] ~ dnorm( a_bar , sigma ) ,

a_bar ~ dnorm( 0 , 1.5 ) ,

sigma ~ dexp( 1 )

), data=dat , chains=4 , log_lik=TRUE )

post <- extract.samples(mSTP)

dens( post$bP , lwd=4 , col=2 , xlab="bP (effect of predators)" )extremely similar predictions between model with predators and model without

- because alphas can learn the behaviours of each tank without an explanation (ie predators)

BUT the variation that the model learns between tanks is very different between models

- predator model has much lower variation in sigma

- its not variation among the tanks, its the variation among parameters, net all the other effects in the model

Multilevel Tadpoles

model of unobserved population helps learn about observed units

use data efficiently, reduce overfitting

varying effects: unit-specific partially pooled estimates (also called random effects depending on discipline)

Varying Effects Superstitions

units must be sampled at random (false - unrelated) - justification for partial pooling is that you learn faster

number of units must be large (false - unrelated)

assumes Gaussian variation (false) - misunderstanding of probability theory. Distributions in statistical models are not claims of frequency distributions of the variables in the real world, they are just priors. Posterior distribution does not have to be Gaussian. A Gaussian prior does not impose a Gaussian posterior distribution.

prior is just a prior

but you can use non-random distributions in multilevel models

Practical Difficulties

how to use more than one cluster at the same time?

how to sample efficiently?

what about slopes? confounds?

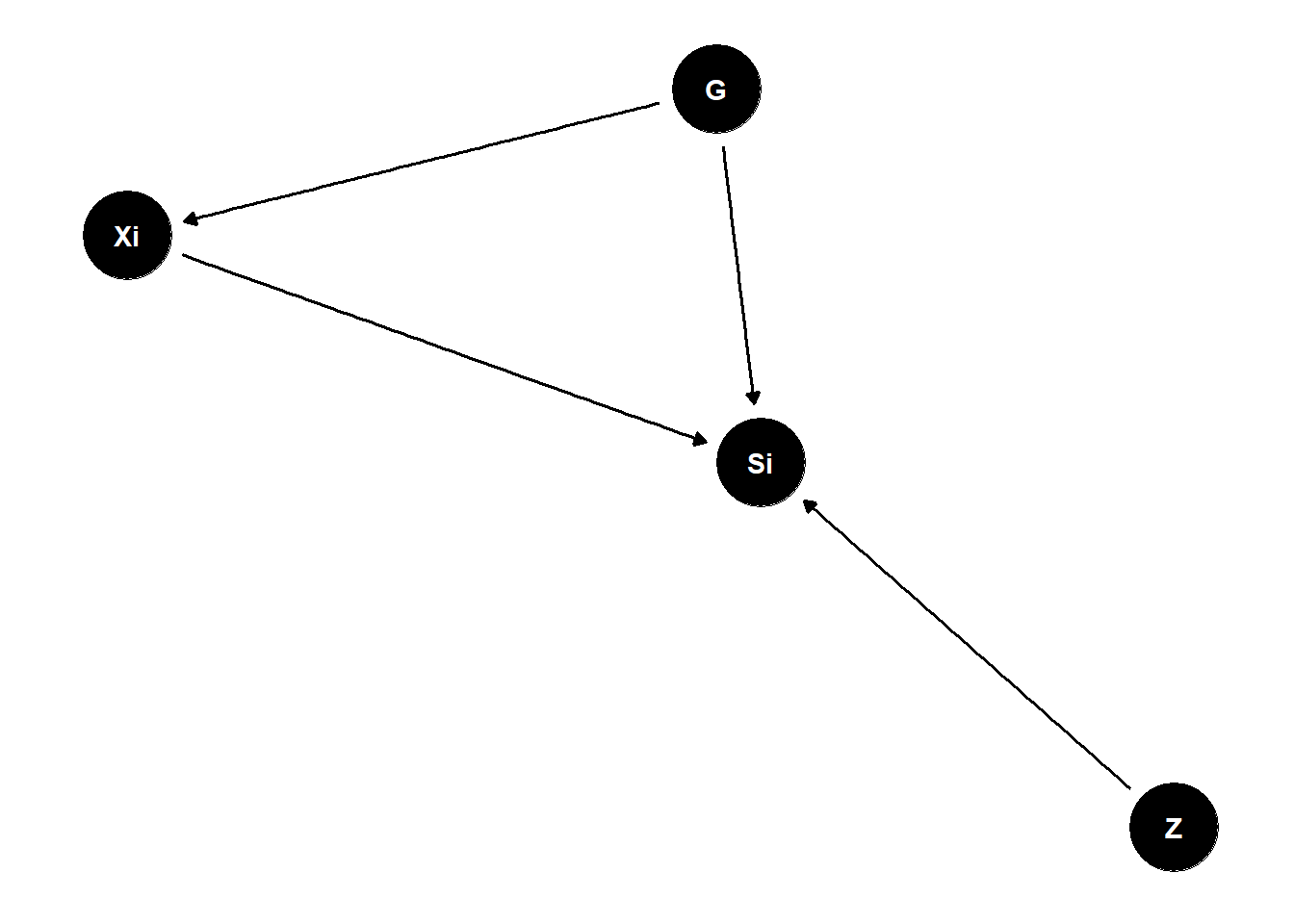

Bonus: Random Confounds

when unobserved group features influence individually-varying causes

- group level variables have direct and indirect influences

very confusing literature

G (tank traits) have direct influences on Si (survival)

Z (group trait) have direct influences on Si (survival)

Xi (individual trait) have direct influences on Si

PROBLEM: G (tank traits) also indirectly influence Si through Xi

multilevel models that account for these confounds = Mundlak Machines

set.seed(8672)

N_groups <- 30

N_id <- 200

a0 <- (-2)

bZY <- (-0.5)

g <- sample(1:N_groups,size=N_id,replace=TRUE) # sample into groups

Ug <- rnorm(N_groups,1.5) # group confounds

X <- rnorm(N_id, Ug[g] ) # individual varying trait

Z <- rnorm(N_groups) # group varying trait (observed)

Y <- rbern(N_id, p=inv_logit( a0 + X + Ug[g] + bZY*Z[g] ) )

table(g)- can use a fixed effects model (estimate a different average rate for each group, without pooling) which soaks up the confounding - but its inefficient and it cannot identify any group-level effects

# fixed effects

# X deconfounded, but Z unidentified now!

precis(glm(Y~X+Z[g]+as.factor(g),family=binomial),pars=c("X","Z"),2)

dat <- list(Y=Y,X=X,g=g,Ng=N_groups,Z=Z)

# fixed effects

mf <- ulam(

alist(

Y ~ bernoulli(p),

logit(p) <- a[g] + bxy*X + bzy*Z[g],

a[g] ~ dnorm(0,10),

c(bxy,bzy) ~ dnorm(0,1)

) , data=dat , chains=4 , cores=4 )

# random effects

mr <- ulam(

alist(

Y ~ bernoulli(p),

logit(p) <- a[g] + bxy*X + bzy*Z[g],

transpars> vector[Ng]:a <<- abar + z*tau,

z[g] ~ dnorm(0,1),

c(bxy,bzy) ~ dnorm(0,1),

abar ~ dnorm(0,1),

tau ~ dexp(1)

) , data=dat , chains=4 , cores=4 , sample=TRUE )should expect your model to have posterior high density regions over the true value

fixed effects model cannot estimate the group level effects

multilevel model pulls intercepts towards each other and thus compromises on identifying the confound so that it can get better estimates for each group

- better estimates for G, worse estimate for X but you can include Z

Mundlak Machine

calculate group average X which is a descendant of the confound (G) SO if we condition on \(\overline{X}_G\) and treat it like a group level variable, it will partly deconfound our model

estimate a different average rate for each group via partial pooling via including group average X

better X but improper respect for uncertainty in X-bar (ignoring quality of Xbar across groups)

# The Mundlak Machine

xbar <- sapply( 1:N_groups , function(j) mean(X[g==j]) )

dat$Xbar <- xbar

mrx <- ulam(

alist(

Y ~ bernoulli(p),

logit(p) <- a[g] + bxy*X + bzy*Z[g] + buy*Xbar[g],

transpars> vector[Ng]:a <<- abar + z*tau,

z[g] ~ dnorm(0,1),

c(bxy,buy,bzy) ~ dnorm(0,1),

abar ~ dnorm(0,1),

tau ~ dexp(1)

) , data=dat , chains=4 , cores=4 , sample=TRUE )can fix the problem of not respecting the uncertainty in X-bar

treat G as unknown and use Xi to estimate

respects uncertainty in G

run two simultaneous regressions

# The Latent Mundlak Machine

mru <- ulam(

alist(

# Y model

Y ~ bernoulli(p),

logit(p) <- a[g] + bxy*X + bzy*Z[g] + buy*u[g],

transpars> vector[Ng]:a <<- abar + z*tau,

# X model

X ~ normal(mu,sigma),

mu <- aX + bux*u[g],

vector[Ng]:u ~ normal(0,1),

# priors

z[g] ~ dnorm(0,1),

c(aX,bxy,buy,bzy) ~ dnorm(0,1),

bux ~ dexp(1),

abar ~ dnorm(0,1),

tau ~ dexp(1),

sigma ~ dexp(1)

) , data=dat , chains=4 , cores=4 , sample=TRUE )can use fixed effects if you are not interested in group-level predictors or prediction

can include average X but it is better to use the latent model

confounds vary a lot - there is no one answer